"Oh, say can you see?” their hopeless voices were asking next, the hammer strokes of metal tongues drowning them out. “The war is over,” said Miss Tanner, her underlip held firmly, her eyes blurred. Miranda said, “Please open the window, please, I smell death in here.” ~ -Katherine Anne Porter, Pale Horse, Pale Ride

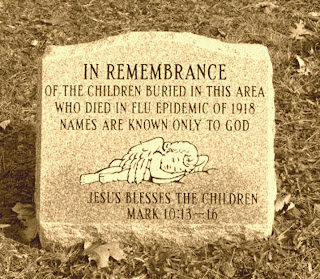

In 1918-19, the world saw the most catastrophic pandemic in modern history. More people died from the H1N1 strain that circulated at the time - Spanish Flu as it became known- than from fighting in World War I.

In the annals of modern medicine, the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 is the standard of virulence against which all other infectious diseases are measured. Historians have long agreed that at least 20 to 40 million people died in a pandemic that reached from the ice floes of Alaska to the jungle villages of Gambia. But because of spotty record-keeping and no definitive diagnostic test at that time, this estimate may be too low. Epidemiologists today look back at a far larger toll—at least fifty million deaths and perhaps up to 100 million.

The influenza struck with frightening speed. Some people woke up in the morning feeling well, became sick in the early afternoon, and died at night. Those who fought off the disease’s initial attack frequently faced a secondary onslaught of bacterial pneumonia lasting a few days. For many it was a matter of dying sooner or later.

|

One-fifth of the world’s population (about two billion at the time) came down with the disease. In the United States, the infection rate was higher—28 percent—resulting in 675,000 deaths, which depressed the average life expectancy by 10 years. | |

| The toll of death worldwide surpassed combat fatalities from all wars of the 20th century. -harvard.edu 1918. Reports of the flu originally came from Fort Devens, Massachusetts where troops were assembling to transfer to Europe to fight in World War I. People traveling by train came into depots where populations were dense, spreading the virus like wildfire through out the state. Outbreaks were occured in White River Junction, St. Johnsbury, Rutland and St. Albans. Barre and Montpelier were the hardest hit in the state. Late summer and into the fall, Vermont was devastated by the "Spanish Influenza" pandemic flu. The disease attacked the lungs, caused high fever, boils and pimples, delirium, horrible pain in the back, arms and legs, and nausea. Those who fought the disease’s first attack often faced a secondary onslaught of bacterial pneumonia lasting a few days; which essentially meant that it was a matter of dying sooner or later. "On September 27th, 1918, the Public Health Service noted that “indefinite reports of influenza at many places have been reported.” During the final week of September, there were over 6,000 cases in the state. By October 4th, influenza could be found throughout the state. The largest outbreaks were at Middlebury, St. Johnsbury, Lydonville, St. Albans, Montpelier, Barre, Randolph and Northfield. Because officials were quickly overwhelmed by the disease, most reports regarding influenza cases and deaths were probably inaccurate. However, it does seem that the disease probably peaked in Vermont during the week of October 12th." -http://www.flu.gov/pandemic/history/1918/your_state/northeast/vermont/ The flu usually ran its course in about 3 weeks time, but could easily be fatal in 3 days or quicker. The medical community was ill prepared for the epidemic and did not have antibiotics and/or antiviral medications for treatment. The most they could do was to treat symptoms of the flu, and try to make those afflicted as comfortable as possible. For those who met their sudden demise, their death was recorded. "So people watched the virus approach, and feared, feeling as important as it moved toward them as if it were an inexorable oncoming cloud of poison gas. It was a thousand miles away, five hundred miles away, fifty miles away, twenty miles away… Wherever one was in the country, it crept closer—it was in the next town, the next neighborhood, the next block, the next room. In Tucson the Arizona Daily Star warned readers not to catch “Spanish hysteria!” “Don’t worry!” was the official and final piece of advice on how to avoid the disease from the Arizona Board of Health. “Don’t get scared!” said the newspapers everywhere. Don’t get scared! they said in Denver, in Seattle, in Detroit; in Burlington, Vermont, and Burlington, Iowa, and Burlington, North Carolina; in Greenville, Rhode Island and Greenville, Mississippi. And every time the newspapers said, Don’t get scared! they frightened." - John Barry "The influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed more people than the Great War, known today as World War I (WWI), at somewhere between 20 and 40 million people. It has been cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history. More people died of influenza in a single year than in four-years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351. Known as "Spanish Flu" or "La Grippe" the influenza of 1918-1919 was a global disaster. The pandemic affected everyone. With one-quarter of the US and one-fifth of the world infected with the influenza, it was impossible to escape from the illness. Even President Woodrow Wilson suffered from the flu in early 1919 while negotiating the crucial treaty of Versailles to end the World War (Tice). Those who were lucky enough to avoid infection had to deal with the public health ordinances to restrain the spread of the disease. The public health departments distributed gauze masks to be worn in public. Stores could not hold sales, funerals were limited to 15 minutes. Some towns required a signed certificate to enter and railroads would not accept passengers without them. Those who ignored the flu ordinances had to pay steep fines enforced by extra officers (Deseret News). Bodies pilled up as the massive deaths of the epidemic ensued. Besides the lack of health care workers and medical supplies, there was a shortage of coffins, morticians and gravediggers (Knox). The conditions in 1918 were not so far removed from the Black Death in the era of the bubonic plague of the Middle Ages." -http://virus.stanford.edu/uda/

1665 Bubonic Plague:

"Ring around the rosies,

A pocket full of posies,

Ashes, ashes,

We all fall down!"

"That Flu Stuff”

The following poem appeared in the December 14, 1918 issue of The Literary Digest:

That Flu Stuff

If you have a tummy-ache,

It’s the Flu!

If you’re weary when you wake,

It’s the Flu!

Is your memory off the track?

Is your liver out of whack?

Are there pimples on your back?

It’s the Flu!

Are there spots before your eyes?

It’s the Flu!

Are you fatter than some guys?

It’s the Flu!

Do your teeth hurt when you bite?

Do you ever have a fright?

Do you want to sleep at night?

It’s the Flu!

Are you thirsty when you eat?

It’s the Flu!

Are you shaky on your feet?

It’s the Flu!

If you feel a little ill,

Send right off for Dr. Pill,

He will say, despite his skill,

“It’s the Flu!”

He won’t wait to diagnose,

It’s the Flu!

Hasn’t time to change his clothes,

It’s the Flu!

For two weeks he’s had no rest,

Has no time to make a test,

So he’ll class you with the rest—

It’s the Flu!

-

Cincinnati Enquirer

The Literary Digest

(14 December 1918)

Following is a account of the flu, in the form of a letter written in 1918 from Fort Deven, Massachusetts. The physician explains to a friend the flu's symptoms and its gruesome reality:

A Letter From Camp Devins, MA

A doctor stationed at Camp Devens, a military base just west of Boston, writes to a friend and fellow physician, of the conditions to be found there as influenza was making its presence felt.

Camp Devens, Mass.

Surgical Ward No. 16

29 September 1918

My dear Burt,

It is more than likely that you would be interested in the news of this place, for there is a possibility that you will be assigned here for duty, so having a minute between rounds I will try to tell you a little about the situation here as I have seen it in the last week.

As you know, I have not seen much pneumonia in the last few years in Detroit, so when I came here I was somewhat behind in the niceties of the Army way of intricate diagnosis. Also to make it good, I have had for the last week an exacerbation of my old “Ear Rot” as Artie Ogle calls it, and could not use a stethoscope at all, but had to get by on my ability to “spot” 'em thru my general knowledge of pneumonias…

Camp Devens is near Boston, and has about 50,000 men, or did have before this epidemic broke loose. It also has the base hospital for the Division of the Northeast. This epidemic started about four weeks ago, and has developed so rapidly that the camp is demoralized and all ordinary work is held up till it has passed. All assemblages of soldiers taboo. These men start with what appears to be an attack of la grippe or influenza, and when brought to the hospital they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of pneumonia that has ever been seen.

Two hours after admission they have the mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies sort of gets on your nerves. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day, and still keeping it up. There is no doubt in my mind that there is a new mixed infection here, but what I don’t know. My total time is taken up hunting rales, rales dry or moist, sibilant or crepitant or any other of the hundred things that one may find in the chest, they all mean but one thing here — pneumonia — and that means in about all cases death.

The normal number of doctors here is about 25 and that has been increased to over 250, all of whom (of course excepting me) have temporary orders — “Return to your proper station on completion of work” — Mine says, “Permanent Duty,” but I have been in the Army just long enough to learn that it doesn’t always mean what it says. So I don’t know what will happen to me at the end of this. We have lost an outrageous number of nurses and doctors, and the little town of Ayer is a sight. It takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce, we used to go down to the morgue (which is just back of my ward) and look at the boys laid out in long rows. It beats any sight they ever had in France after a battle. An extra long barracks has been vacated for the use of the morgue, and it would make any man sit up and take notice to walk down the long lines of dead soldiers all dressed up and laid out in double rows. We have no relief here; you get up in the morning at 5:30 and work steady till about 9:30 p.m., sleep, then go at it again. Some of the men of course have been here all the time, and they are tired.

If this letter seems somewhat disconnected overlook it, for I have been called away from it a dozen times, the last time just now by the Officer of the Day, who came in to tell me that they have not as yet found at any of the autopsies any case beyond the red hepatitis stage. It kills them before it gets that far.

I don’t wish you any hard luck Old Man, but do wish you were here for a while at least. It’s more comfortable when one has a friend about. The men here are all good fellows, but I get so damned sick o’ pneumonia that when I eat I want to find some fellow who will not “talk shop” but there ain’t none, no how. We eat it, sleep it, and dream it, to say nothing of breathing it 16 hours a day. I would be very grateful indeed it you would drop me a line or two once in a while, and I will promise you that if you ever get into a fix like this, I will do the same for you.

Each man here gets a ward with about 150 beds (mine has 168), and has an Asst. Chief to boss him, and you can imagine what the paper work alone is — fierce — and the Government demands all paper work be kept up in good shape. I have only four day nurses and five night nurses (female) a ward-master, and four orderlies. So you can see that we are busy. I write this in piecemeal fashion. It may be a long time before I can get another letter to you, but will try.

Good-by old Pal,

“God be with you till we meet again”

Keep the Bouells open,

Roy

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)